DRIFTING THOUGH THE ENDLESS GARDEN

Plants have been models and themes of art since antiquity. The Middle Age tradition of encoding human virtues in flowers flourished in Renaissance times, as flowers and plants in art became attributes of deities or assumed symbolic codes as something like pictorial metonyms. At the beginning of the 18th century, botany became a fashion and in art the Pre-Raphaelites made ample use of the manifold symbolism of plants, flowers and blossoms. For them the flowers became “the universal moralists … the emblems alike of feasting and mourning, of speech and silence, of sorrow and hope, of grief and love.” [1]

Some of the works from CoMA present at the exhibition © Elmar R. Gruber

Some of the works from CoMA present at the exhibition © Elmar R. Gruber

A mystified romantic view of nature had anchored a plant code in the hidden life of man. Deep inside, in the thicket of the soul’s imagery lay the ephemeral shadowy gardens, the place of bewildering metamorphoses, the inconceivable realm where glittering meadows and primeval forests expand, evolve constantly, emerge and vanish. In the course of the 19th century, this inner reality was explored from new perspectives, the proliferating world of inner images was given new names and measured out: the soul, the unconscious, the subliminal self (Frederic W. H. Myers), the subconscious self (Pierre Janet). Myers found that “hidden in the depth of our being is a rubbish-heap and a treasure-house." [2] It was in artistic creativity that he saw the most striking, but also the most mysterious manifestation of the subliminal self. A finding confirmed at the turn of the century by Theodore Flournoy’s groundbreaking study of the spiritualist medium Hélène Smith [3] by revealing the workings of the autonomous creativity of the psyche through what he called the “ludic” or playful function of the unconscious.

Two works by Max Ernst © Joachim Werkmeister

Two works by Max Ernst © Joachim Werkmeister

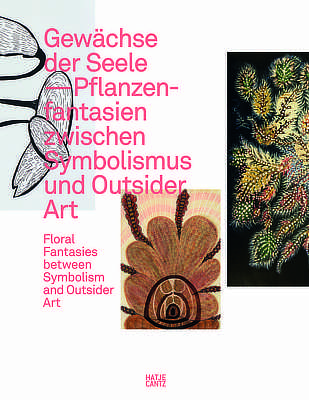

At present, an ambitious exhibition project entitled “Floral Fantasies between Symbolism and Outsider Art” at Ludwigshafen and other locations in Germany sets out to trace how the hypertrophic flood of images of the soul along with transpersonal compartments enclosed within it were and are unfolded in artistic processes. The center of the project is the Wilhelm-Hack-Museum in Ludwigshafen. There, the main focus is placed on the thematic and formal relations between symbolist and surrealist works on the one hand and works that have been created outside the acknowledged production of art on the other. Other sites taking part in this project with major exhibitions confronting the subject from various angels are the Prinzhorn Collection and the Museum Haus Cajeth, both in Heidelberg, the Gallery Alte Turnhalle in Bad Dürkheim, and zeitraumexit in Mannheim.

Curiously enough, the main German title of the exhibition “Gewächse der Seele” has been left untranslated in the English rendering. Apparently because the subtle and complex connotations expressed in the German noun “Gewächse” cannot be adequately reproduced in an English term. It would read a bit awkwardly something like “Excrescences of the Soul”. But that's exactly what this ambitious project is aimed at: The unfoldment of pictorial profusions, excesses, proliferations emerging from a psychic process of fermentation.

The Collection of Mediumistic Art is represented with numerous loans to the Wilhelm-Hack-Museum and for obvious reasons I am exclusively concentrating on this part and aspect of the exhibition.

The stage is set by the access to the exhibition spaces: A wide staircase leads down as if descending into the shadowy realms of the soul, where it is quieter but also more colorful and above all surprising. In this underworld, images of unheard-of vegetations are ceaselessly in the making, a world of endless changing allusions that never seem to attain clearly determined, definitive forms. Something constantly seems to be born and discarded, unknown forms proliferate from familiar ones, only to transform, negate themselves, or disappear.

Georgiana Houghton and works by the surrealists in room 1 © Joachim Werkmeister

Georgiana Houghton and works by the surrealists in room 1 © Joachim Werkmeister

Already in the first room the boundaries drawn by the art-historical canon are blurred. Mediumistic works by Georgiana Houghton and Victorien Sardou enter into dialogue with automatic drawings by the group of surrealists. Concepts believed to be sound and stable seem turned upside down. Houghton's abstract swirls of color and Sardou's finely executed etchings of fantastic plant architectures are impressive in their mastery and perfection, while the surrealists' drawings seem still in search of an appropriate form, with Yves Tanguy's network of ghostly outlined flying lines and one of those playful collectively assembled drawings that became known as “exquisite corpse”.

The first spiritualist artist in Victorian England to put flowers on paper as all-encompassing symbols and expression of an otherworldly existence in the intermediate realm was Elizabeth Wilkinson. In his book Spirit Drawings: a Personal Narrative (London, 1858), her husband, William M. Wilkinson, laid down a spiritualistic explanation of the flowers and blossoms drawn as messages from the afterlife by his wife's hand. This book provided something of an interpretative framework for representations of plants in mediumistic drawings for other “spirit artists” in Victorian Britain like Anna Mary Howitt and Georgiana Houghton. Houghton understood her floral watercolors that in the course of time developed freely into radiant abstract images of layered meandering lines and dots mainly as symbolic representations of individual thoughts or emotional states or the “spiritual character” of an individual. Yet at the same time such mediumistic works were considered as faithful representations of the flora in the otherworldly realms.

The adjacent rooms of the exhibition show how the growth of branches and foliage, of buds and blossoms as a projection screen of unconscious creations develops a life of its own and dominates the picture surface. There, finely nuanced, shimmering small landscapes by Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis stand their ground alongside the vigorous large-format “Large Marguerites” by Séraphine Louis, applied in rich colors. Subsequently, one passes through a magnificent selection of surrealist primeval forests among others by Max Ernst, Paul Klee, André Masson, and René Magritte. They are displayed quite naturally alongside works by outsiders like Aloïse Corbaz, Miloslava Ratzingerova and mediumistic artists such as Josef Kotzian and Nina Karasek.

Drawings by Miloslava Ratzingerova (left), Nina Karasek and Madge Gill © Joachim Werkmeister

Drawings by Miloslava Ratzingerova (left), Nina Karasek and Madge Gill © Joachim Werkmeister

You may follow the didactic scheme of the exhibition or let yourself be carried away, as if floating along in a gentle subterranean river. While passing by you will constantly acquire new views of mysterious vegetations, in which the personal intermingles with the transpersonal. It seems as if the paintings and drawings are touching the ineffable as they try to communicate something essential about inner life from the region of transition, at the threshold from which only a visual language immersed in mystery can tell.

The viewer may watch how the subtext of manifold correspondences of an archetypal symbolic language, this widely ramified code of signs, expressed in mediumistic works, gradually was assimilated by established trained artists, how the symbolists' rich treasure trove of art-historical traditions was informed to some degree by the spontaneous artistic expressions from outsiders. The symbolists, like later the surrealists, had strong inclinations towards occult and esoteric currents and consequently towards the phenomena of somnambulism and mediumism. But apparently it wasn’t the individual works of mediumistic artists that had a major or direct effect on them; only a few of those were actually known. What came into the focus of artists at the end of the 19th century were rather the “techniques” employed by the mediumistic artists to accomplish such uncontrived, raw artistic creations unintentionally arisen from a temporarily disengaged mind devoid of concepts. They became aware of how much artistic expressiveness was impoverished if it was reduced only to the elements that the artist is aware of, about which the conscious ego is the master, as Maurice Denis put it, and who came to the conclusion: “That is why it is important to be ignorant and empty.” [4]

In search for an appropriate expression for the great mysteries of life that take place within the human being, artists experimented more and more with practices for inducing mediumistic states. The appropriation of the techniques of the spiritualistic mediums is even more evident with the surrealists. For them, the fascination with “artworks from the beyond” – which their mouthpiece André Breton admittedly attributed only to a beyond of the threshold of the conscious layers of the psyche – consisted of the circumstance that this art is not made, but arises by itself; where the artist watches its appearance in amazement. An autopoietic process, to a certain degree beyond the reach and intervention of conscious control.

Odile Redon in the room of metamprophes © Joachim Werkmeister

Odile Redon in the room of metamprophes © Joachim Werkmeister

The heart of the exhibition is a womb-like central space, appropriately entitled “Metamorphoses”. This epicenter is a veritable alchemist's kitchen, the matrix of great transformations, where hybrid creatures of plants, animals, and humans are created. It is the laboratory in which a mythopoietic faculty tests its own power. In the abyss of this unus mundus, the elegant and the monstrous, the fantastic and the grotesque, the naive and the refined constantly coalesce. Many small-format works are gathered here that force the viewer to step closer in order to appreciate how imaginative hybrid beings in the mediumistic works of Käthe Fischer and Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz engage with related images by Jan Toorop, Paul Klee and Toyen (Marie Čermínová) and, while ethereal beings of Fernand Desmoulin, emerging with verve from a realm of the indefinite, reveal an urgent and disturbing restlessness of the mind, Odile Redon's pastels abduct the spectator into a dreamlike, quiet and lyric compartment of the inner realms.

Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz (left), Jan Toorop and Käthe Fischer (right) © Joachim Werkmeister

Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz (left), Jan Toorop and Käthe Fischer (right) © Joachim Werkmeister

Leaving this room and entering the last spacious hall with impressive works by Hilma af Klint, Madge Gill, Augustin Lesage, Therese Vallent, Babara Honywood and others, almost exclusively mediumistic, one may think to have gained insight, albeit fleeting and uncertain, into the meaning of the infinite digression manifest in the mediumistic works. Here, these are above all representations of mandala-like structures, which arise almost naturally from the shape of a blossom and sometimes follow geometrically strict patterns, occasionally appearing even in neatly elaborated ornamental lines, as if drawn with stencils, but at times also proliferating in eccentric organic opulence or emerging as abstract vibrating color circles. Intuitively, one recognizes that in this fluctuating dynamic exchange between center and periphery, a mystery is being traced that is basically present in the subliminal mind of every human being. You can’t get close to it unless you let it happen. The place from which these mandala-like “excrescences of the soul” emerge has no location. It only exists as a network of relations.

Therese Vallent, Anna Hackel, Scottie Wilson, surrealist collective drawing, Adda Ducháčová (from left to right) © Joachim Werkmeister

Therese Vallent, Anna Hackel, Scottie Wilson, surrealist collective drawing, Adda Ducháčová (from left to right) © Joachim Werkmeister

Madge Gill (left) and Augustin Lesage (right) © Joachim Werkmeister

Madge Gill (left) and Augustin Lesage (right) © Joachim Werkmeister

Notes:

[1] Debra N. Mancoff, Flora Symbolica: Flowers in Pre-Raphaelite Art. New York: Prestel, 2003, p.147.

[2] Frederic W. H. Myers, Human Personality and its Survival of Bodily Death. Vol. 1, London: Longmans, Green, 1903, p. 72.

[3] Theodore Flournoy, Des Indes à la planète Mars. Etude sur un cas de somnambulisme avec glossolalie. Paris: Alcan, 1900.

[4] Maurice Denis, Journal, Vol. II (Sept. 1915), in : Maurice Denis, Le ciel et l'Arcadie. Jean-Paul Bouillon (Ed.), Paris 1993, pp. 177-78.

text © 2019 Elmar R. Gruber

Exhibition Catalogue

Ed. Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen

Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2019

300 pages, 340 illustrations

ISBN 978-3-7757-4534-5

text © 2019 Elmar R. Gruber